The Power of Parenting with Empathy

It is so important to let kids know that we value their feelings. This improves their sense of self-worth and self-esteem. Dr. Fay clearly remembers one of the many times his dad, Jim, showed that he valued Dr. Fay’s feelings, and it really stuck with him: “I was just 10 years old at the time, and our family was having dinner with Dr. Cline who lived nearby. My dad and Dr. Cline were grousing about how their teachings about limits and accountability only worked in half the kids. They couldn’t figure out why the same strategies didn’t work for the other half of the kids, who basically ended up just disliking their parents more than they already did. All of a sudden, they turned to me and asked, ‘What do you think, Charles?’”

“‘Who, me?” I asked. I didn’t have an answer for them, but the fact that these two grown men with decades of experience wanted my input made me feel special.”

They eventually found the solution they were seeking, and in part, it came from observing the actions of a woman who worked in the school administration office. Mrs. MacLaughlin was a strong but loving woman who was the first person students visited when they had an “emergency” like a forgotten lunch, lost coat, scraped knee, or a hassle with another student. Students in that school believed that all such “crises” required a quick rescue call to one or both of their parents—and these were the days before cell phones.

As they begged to use the office phone, Mrs. MacLaughlin would smile sweetly, look into their eyes as if they were the most precious thing on earth, and say, “Oh honey, what happened?” The kids would describe the problem, she’d listen with great interest, and then she’d respond with empathy by saying:

“Oh, that’s gotta feel so bad. It’s never any fun to have a problem like that. It’s sad, but I can only let you use the phone if there is an emergency. If any kid can handle this, though, you certainly can.”

The kids generally figured out how to solve their problems on their own without using the phone, leaving them full of self-confidence and love for Mrs. MacLaughlin. Jim Fay and Dr. Foster Cline soon discovered the key to making the Love and Logic approach really work: empathy.6 Mrs. Mac always provided a strong dose of this magic before she set a limit or held a student accountable for their actions. This showed the students that she valued their feelings.

Empathy opens a child’s heart and mind to learning, whereas anger shuts the door on learning and relationship.

Anger vs. the Power of Empathy

Empathy, when done correctly, sends a message of love and competence. Some parents think that raising their voice or unleashing ultimatums is the way to get kids to toe the line. It might scare kids into submission, but it comes at a price. Kids whose parents routinely lose their temper or yell at them are vulnerable to a host of consequences that rob mental strength, including:

Feeling stressed, which has negative implications for brain development

Blaming themselves for whatever is making their parent mad

Responding to a parent’s anger with aggressive behavior

Having trouble sleeping

Physical ailments, such as stomachaches

Increased risk for mental health issues later in life

Even more concerning, harsh parenting practices also negatively impact how the brain develops and how it functions. A 2021 study found that frequently yelling or getting angry at children is associated with children having a smaller brain in adolescence.7 When it comes to the brain, size matters.

When a parent gets angry, the child’s brain can view it as a threat. This fires up the amygdala, a brain region that is associated with emotions like fear and anxiety and that is linked to the fight, flight, or freeze response. Guess what this does to the thinking regions of the brain in the prefrontal cortex—it shifts activity away from the thinking areas and makes kids more likely to react with heightened emotions.

Of course, all of us lose our temper once in a while, but there are simple strategies you can use to calm anger. For example:

Take a few deep breaths. Gaining control of your breath can help soothe irritability and deliver more oxygen to your brain to help you respond more rationally to a situation. As soon as you begin to feel anger rising, take a deep breath, inhaling for four seconds, hold it for one second, then exhale for eight seconds. Repeat this 10 times, and you’ll feel more at peace.

Know your triggers. Keep track of when you get mad. Is it when you haven’t eaten for too long? Is it when you’ve had a stressful day at work? Is it when you haven’t gotten enough sleep? When you know your vulnerable times, you can make a plan to circumvent anger before it starts.

Take a time-out. If you feel like you’re going to lash out in anger at your kids, simply say, “I need a time-out,” and take a few moments for yourself. Going for a quick walk, doing a few stretches, or listening to some happy tunes for just a few minutes can often be enough to defuse anger.

Empathy, on the other hand, is far more powerful and beneficial than anger. Empathy is our ability to sense what others feel. In dealing with your kids, empathy pays great dividends. Findings from a 2020 study show that parental empathy enhances kids’ social competence, which is associated with reduced risk of emotional and behavioral problems.8 Increased empathy also leads to an important side effect: accountability. Research9 shows that empathy also plays a role in brain function and activates areas involved in cognitive skills,10 learning, and bonding.

Empathy vs. Sympathy

Empathy is often confused with sympathy. The two couldn’t be more different. While empathy is being able to understand and share another person’s feelings, sympathy is feeling sorry for someone else. Here are a few examples that show the difference between the two:

Sympathy: “It’s too bad you didn’t get chosen for the dance squad. Maybe if you take more lessons, you can make the squad next year.”

Empathy: “That must feel bad not getting chosen for the dance squad. I’m here for you if you want to talk about it.”

Sympathy: “That’s terrible that your friend said something mean to you. At least you have other friends.”

Empathy: “It’s OK to feel bad when someone says something mean. I get it.”

Each is largely communicated through subtle yet very powerful factors, such as tone of voice, facial expression, and other forms of nonverbal communication. Sympathy creates lack of confidence and fear. Empathy builds confidence and resilience.

When you consistently send messages of love to your child, they grow up self-confident and assured. With the feelings of security and safety that come from these loving messages, you give your child’s brain, sense of self, and mental strength room to develop.

7. Sabrina Suffren et al., “Prefrontal Cortex and Amygdala Anatomy in Youth with Persistent Levels of Harsh Parenting Practices and Subclinical Anxiety Symptoms over Time during Childhood,” Development and Psychopathology 34, no. 3 (August 2022): 957–968, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33745487/.

University of Montreal, “Does ‘Harsh Parenting’ Lead to Smaller Brains?” ScienceDaily, March 22, 2021, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/03/210322085502.htm

8. Kun Meng et al., “Effects of Parental Empathy and Emotion Regulation on Social Competence and Emotional/Behavioral Problems of School-Age Children,” Pediatric Investigation 4, no. 2 (June 2020): 91–98, https://mednexus.org/doi/full/10.1002/ped4.12197.

9. Jean Decety and Meghan Meyer, “From Emotion Resonance to Empathic Understanding: A Social Developmental Neuroscience Account,” Development and Psychopathology 20, no. 4 (Fall 2008): 1053–1080, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18838031/

10. Kamila Jankowiak-Siuda, Krystyna Rymarczyk, and Anna Grabowska, “How We Empathize with Others: A Neurobiological Perspective,” Medical Science Monitor 17, no. 1 (2011): RA18–RA24, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3524680/.

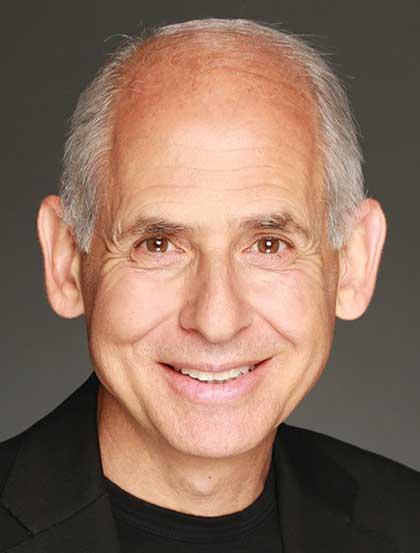

Adapted from Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young Adults by Daniel G. Amen, MD, and Charles Fay, PhD, releasing in March 2024.